This blog will take you through what is involved in preparing and submitting a planning application in a conservation area.

The focus is on larger more complex applications rather than residential applications but the information below will help everyone considering a project in a conservation area.

In the past planning was a much simpler process. These days, with increasing pressures on the historic environment, planning in conservation areas requires serious expertise. The project team must be able to design a building and landscape that is acceptable to the local authority.

There are frequently tensions in a project between energy conservation and heritage or between development and protection of a conservation area. The local planning authority and residents may be hesitant to accept your proposed development. It is our job to resolve these tensions.

Your application will undergo some serious scrutiny before, during and after its submission. Interested parties will review the proposed projects:

- Impact on neighbouring buildings.

- Contribution to placemaking (public space, the adjacent streets and parks).

- Impact on local infrastructure.

In this blog I have outlined four principles and four tips to make sure your application has the best possible chance of success. You will need a team of professionals who can write your brief, advise you on risks and costs and advise you on the potential social value of your project using the three pillars of:

- Economic

- Social and

- Environmental impacts.

By comprehensively addressing social value you will make the process much smoother and end up with a better building or master plan.

How do you know you are in a conservation area?

All councils in the United Kingdom will have information on Conservation Areas including maps. You and your advisors will need to review the maps to check if you are in a conservation area or type your postcode into this Government site to find more information.

If you are then your team will need to carefully read all the documentation about the character and heritage of the area that will have been published by the local authority and local history groups.

Important note: If your building is listed, there are extra steps you need to go through during the planning process, and listed building consent must be applied for as well as planning permission.

This blog does not cover the listed building application process but if you do need help with a listed building we have experience and can help.

What happens to value when you gain permission?

This is the first major hurdle you might face on your project. The value of your site will significantly increase once planning is granted, so gaining planning permission is a major milestone.

What about permitted development and article 4 directions?

You can perform certain types of work without needing to apply for planning permission. These are called ‘permitted development rights’. These rights are granted by Parliament.

In some designated areas, such as a conservation area or a national park, permitted development rights are more restricted. An article 4 direction enables the Secretary of State or the local planning authority to withdraw specified permitted development rights across a defined area.

This can be introduced when the local council considers that the character of an area of acknowledged importance could be threatened.

Where there are article 4 directions in place, you will have to submit a planning application for your project.

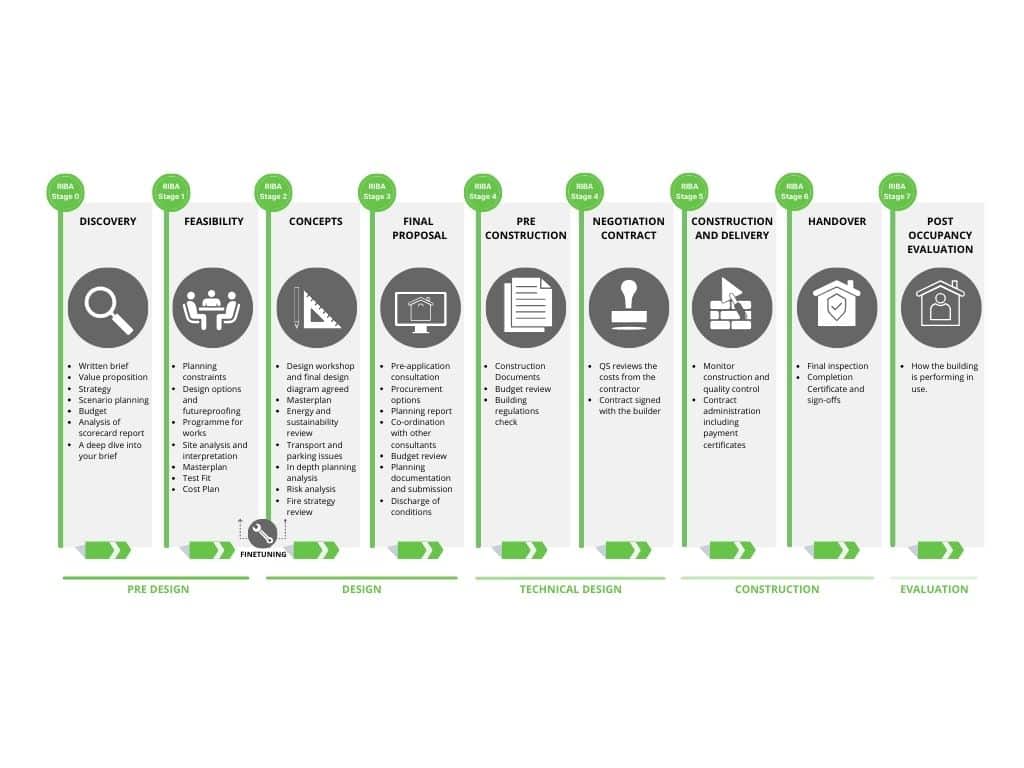

Once you and your team have determined you are in a conservation area and you have discussed your brief with your architect/ design advisor and you have written it down then you can commence the feasibility phase which involves analysis and testing some initial ideas to see what works best.

What are the key principles for gaining planning permission?

Principle 1 Analysis:

Analysis involves assessing planning risk so it can be mitigated as soon as possible.

Each planning application should be interpreted in context, as solutions that work well in one area may not be acceptable to the local authority in another.

All submissions should be designed to fit the particular circumstances of your site. The analysis will commence in the feasibility stage and we will strategise how to tackle the seemingly unresolvable tensions that can exist in projects in conservation areas.

This principle involves reviewing the impact of any potential development on the neighbouring properties and the ‘character’ of the site.

There will be several issues that you and your design team need to consider in depth:

- The bulk and size of the development,

- The impact on the natural light available to neighbouring properties.

- Any increase in traffic and noise that may affect the area.

Because the planning system is influenced by precedents, to assess the chances of getting permission we need to know the details of the plot and examine how the local authority has treated similar applications in the past.

We use our knowledge of both national and local planning guidance, including relevant local transport and environmental policies, to make decisions about what we think it will be possible to achieve on your site.

It is important your team is thorough in the analysis of all policies to ensure something of key importance is not missed. Integral to this principle is deciding whether the precedents that have been established are reasonable or we should try and persuade local authorities to move away from their past judgements.

Principle 2 Storytelling:

Your success in building a convincing value proposition is through storytelling. The story you present to the public needs to outline how the project will benefit the community. This is particularly important if you are building in a conservation area.

Storytelling work begins in the discovery and feasibility stages and will be explained in the Design and Access Statement (DAS). The DAS is a comprehensive report outlining the process that has led to the development proposal. It is presented in a clear and structured way in a written document with diagrams and forms part of the documents produced in the Final Proposals stage that are submitted to the LPA.

Your design team needs to anticipate everything that the local planning authority will consider relevant.

It presents a convincing argument as to why planning permission should be granted, and it is where your team can explain the value of your project in detail, including the economic, social and environmental benefits of the scheme.

See Tip 4 below for more detailed information on Social Value.

The more compelling your story, the better your chance of success.

Principle 3 Collaboration:

The fate of your planning proposal is in the hands of planning officers and/or the planning committee.

One of the potential advantages of a system as complex as planning is that through dialogue, empathy and negotiation it is possible to pick up hints, read between the lines and make the changes required to get your project over the line.

Consultation with the local authority is essential in all complex projects so that both you and your design team can fully understand what all the constraints are, and can benefit from the local authority planner’s knowledge of the area and the local design guides.

To successfully navigate planning, you should commission your architect to build a great team of professionals, including a planning consultant, engineers and a transport consultant, who have ideally worked together in the past.

What can you do:

- Build relationships: Having a good relationship with local councillors and planning officers and discussing your project with them to gauge support for your proposals will help you assess if there is likely to be significant opposition to your proposals.

- Undertake a pre-application meeting: This is a meeting with the council where you can discuss in depth the project and gain feedback from the various experts within their team. Normally the pre-application meeting takes place in Concept Design Phase.

Principle 4 Re-Design:

Once we have collaborated with, listened to and received feedback from all the interested parties, particularly the local planning authority, your project may need to be reworked and transformed to accommodate the feedback. This occurs in the Final Proposals Phase. Only then can the scheme be submitted for planning.

Important note: You and your team need to be flexible and be able to adjust and sometimes rethink applications to consider the views of the local authority. If there is a blockage you need to speak to an experienced design advisor to help.

We offer this service to help clients unlock projects and gain the permissions they need.

Tip 1: Engage a full team to consider all aspects of the application

Why is this important?

If you don’t engage a full team, then vital aspects of the project may not be adequately interrogated during the early stages of a project.

If vital aspects of the proposal are not considered at the right time this can lead to major problems including re-working of drawings down the line. This costs money and time.

Our key collaborators on complex and large projects in conservation areas include:

- Heritage Consultant: depending on the context and building we sometimes work with heritage consultants with in-depth knowledge of relevant legislation. A heritage consultant is not always required but we will advise if we think one is necessary. We normally work with Sara Davidson from Heritage Collective who has expert knowledge on working with listed buildings and in Conservation Areas.

- Planning consultants advise on planning policy and what is likely to be acceptable at a very early stage. They are not always required but like the heritage consultant above they can be invaluable. We will advise if they are needed and who the best people are.

- Some engineering input maybe required for a commercial project. An good environmental engineer can help us to achieve your energy and sustainability goals and improve your chances of gaining planning permission.

- A transport consultant will normally be vital to assessing the impact of any commercial development. If you are proposing an extension to a club or school or commercial building then it will be important to assess the impact of increased traffic on the local infrastructure and residents.

Note: residential applications are simpler and normally do not require a large team.

Tip 2: Community Engagement

Why is this important:

Make sure your team helps you consult with the local authority. This is essential in a densely packed urban setting in a conservation area. If you do not take into consideration the views of local people you may fail to capture their concerns and the social value in the project. Your architect can advise how to approach public consultation.

Tip 3: Carefully consider landscape and biodiversity as well as the urban context.

Why is this important?

This could be key part of your scheme if your building sits in a landscape or park. Landscape plays a key role in views to your scheme, the approach to the building, the types of spaces that are between buildings and the richness of the biodiversity of your site.

Most buildings in a conservation area will sit in a particular urban context that has a grain and character based on when it was constructed. It could be that if you are in central London that you are in an area with predominantly Georgian buildings and garden squares. Every part of the city has its own unique character which needs to be understood.

Tip 4: Articulate the Social Value of your project.

Why is this important in a conservation area?

Social Value is used to demonstrate and evaluate the impact of design on people and communities. It includes the social, environmental and economic benefits to society that are a result of your project. These will form part of your story and be articulated in the DAS. This is important in a commercial project and would not normally be part of a householder application.

The social value of architecture includes:

- Developing connections with nature.

- Offering opportunities for an active lifestyle.

- Creation of jobs and apprenticeships.

- Wellbeing generated by design and healthy communities.

- Designing with the community and creating local employment.

- Learning developed through construction.

- The wider community benefits from the asset.

- Focus on placemaking and creating places for the community to meet.

- Creation of employment for young and disadvantaged people.

- Creating opportunities for training and local employment.

- Preservation of cultural heritage and identity through renovation fostering a sense of continuity and pride in the community.

- Sympathetic renovation will improve the visual environment and and promote a positive identity for the neighbourhood.

- Do you believe the building might reduce crime rates in the local area, reduce social segregation or provide employment?

- Reduction in crime rates and social segregation in the local area.

What can you do:

- Consider Social Value from the beginning: Our advice would be to consider the social value of you project from the outset. This will help guide your thinking and the development of your brief to the design team. The design team will then be able to take your initial ideas and develop these into a compelling story for your application.

A example of how to use storytelling to gain permission?

Private members club: Banqueting Hall Brent

The Banqueting Hall Brent project was an extension to an existing mock Tudor pavilion located in the Northwick Circle Conservation Area in the London borough of Brent. The brief included a large banqueting hall for 350 people, flexible meeting rooms with independent access, a new bar and a commercial kitchen.

In this project there was tension between development and conservation, and between heritage and energy-saving strategies. It was our job to resolve the conflict between the client’s brief for a large extension and the local authority’s concern for the impact of the extension on the conservation area through increased traffic, noise from large events or the size of the proposed building.

Our analysis involved ‘pulling’ the existing building apart to reveal its underlying logic. We spent a lot of time researching the history of the site, the development of the centre and the character of the area around our building.

The story commenced with ideas based on how the project would create social value through the employment of local people, the use of local materials, the sympathetic renovation, the enhancement of the landscape around the site, the engagement with businesses in the area. It was also important to understand our client’s business operation and how the project would ensure the viability of their business into the future.

The design focused on the future health and wellbeing of staff and visitors, and on the quality of spaces we could provide. We achieved this by opening up the building to natural light and views over the landscape and providing exceptional internal air quality through an innovative natural ventilation system.

The story developed through diplomacy and building rapport with the conservation officer and planner. By engaging with the local authority during the pre- and post-application meetings, we understood their interpretation of the existing building and their views on how it might be transformed. Allowing the local authority to influence the design made them co-creators.

We engaged with the local authority through a pre-application meeting with the local authority to openly debate the design, heritage and planning issues. These meetings with the planners and the conservation officer helped shape the design of the centre and helped our client understand what was possible.

Following written feedback from the planners and the conservation officer, we re-designed the building and redistributed the accommodation to reduce the bulk of the proposals. We gained agreement on the design approach from the conservation officer before our formal submission.

The four principles helped us gain permission in August 2021.

Key ideas and takeaways.

It is important to understand the value of the project to you and your customers.

- There are four principles that are critical during the planning phase of your project: analysis, storytelling, collaboration and redesign.

- Make sure your team has an intimate knowledge of context including landscape.

- Landscape enhancements may be important aspect of your story.

- Consider social value of your project from an economic, social and environmental point of view.

- Sustainability is important because it will reduce your ongoing energy costs, and because it demonstrates a commitment to quality and to lowering our collective carbon footprint.

- There may be conflicts in conservation areas between energy conservation and heritage, which your design team needs to resolve to achieve a positive outcome.

- Build a strong value proposition that will appeal to stakeholders, including the local authority and neighbours.

Contact us if you need help getting planning permission in a conservation area today!