This blog will take you through what is involved in preparing and submitting a planning application in the Green Belt or in Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The focus is on larger more complex applications rather than residential applications, but the information below will help everyone considering a project in the Green Belt.

In the past planning was a much simpler process. These days, with increasing development, planning in the Green Belt requires expertise. The project team must be able to interpret local and national planning policy and then design a building and landscape that aligns with policy requirements. Only then will you have a chance of gaining permission from the local authority.

Green Belt

There are frequently tensions in a project between development and protection of the openness of Green Belt. The local planning authority and residents may be hesitant to accept your proposed development. It is our job to resolve these tensions.

Your application will undergo some serious scrutiny before, during and after its submission. Section 13 (Protecting Green Belt Land) of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) states that the Government attaches great importance to Green Belts. The fundamental aim of Green Belt policy is to:

- To prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open.

- To prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another

- To retain the openness of the Green Belt.

- To prevent inappropriate development that is harmful to the Green Belt.

- To preserve the setting and special character of historic towns.

- To assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)

In planning terms, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) are designated landscapes that are recognized for their exceptional natural beauty.

They are protected areas that aim to conserve and enhance the beauty of the landscape, taking into account their natural features, wildlife, and cultural significance.

What Are the Restrictions on Building in AONBs?

When it comes to development and building in an AONB, there are significant planning restrictions and considerations due to the need to protect the landscape’s beauty and ecological value. These restrictions typically include:

- Stricter Planning Controls: New development is highly regulated and must demonstrate that it conserves and enhances the natural beauty of the area.

- Development should be in keeping with the local character and landscape. This means that any new buildings, structures, or changes to the environment should not detract from the scenic quality of the AONB.

- Any development in an AONB requires planning permission and is likely to be scrutinized more rigorously than in other areas.

- The Local Planning Authority will typically require a detailed assessment of how the proposal will affect the area’s natural beauty, including how the project’s design, scale, and materials fit into the landscape.

- Developments must avoid significant adverse effects on the natural environment, wildlife habitats, and scenic vistas. Measures to mitigate the impact of the development (e.g., landscaping, tree planting, or changes to building materials) are often required.

You will need an ecologist and landscape architect on your team to assist with this.

- Design, materials, and landscaping should reflect the character of the surrounding area. For example, traditional building materials may be preferred in areas where this style is characteristic of the landscape.

- Your architect will need to understand the vernacular buildings in your AONB so that the design solution is appropriate.

- The development should not obstruct or alter views that are valued as part of the landscape.

How to gain permission in Green Belt and AONB

In this blog I have outlined four principles and four tips to make sure your application has the best possible chance of success.

You will need a team of professionals who can write your brief, advise you on

- Planning risk

- Development Costs

- Very special circumstances (VSCs) needed to justify the development and

- The potential social value of your project.

Social value will be assessed using the three pillars of economic, social and environmental impacts.

By comprehensively addressing social value you will make the process much smoother and end up with a better building or master plan.

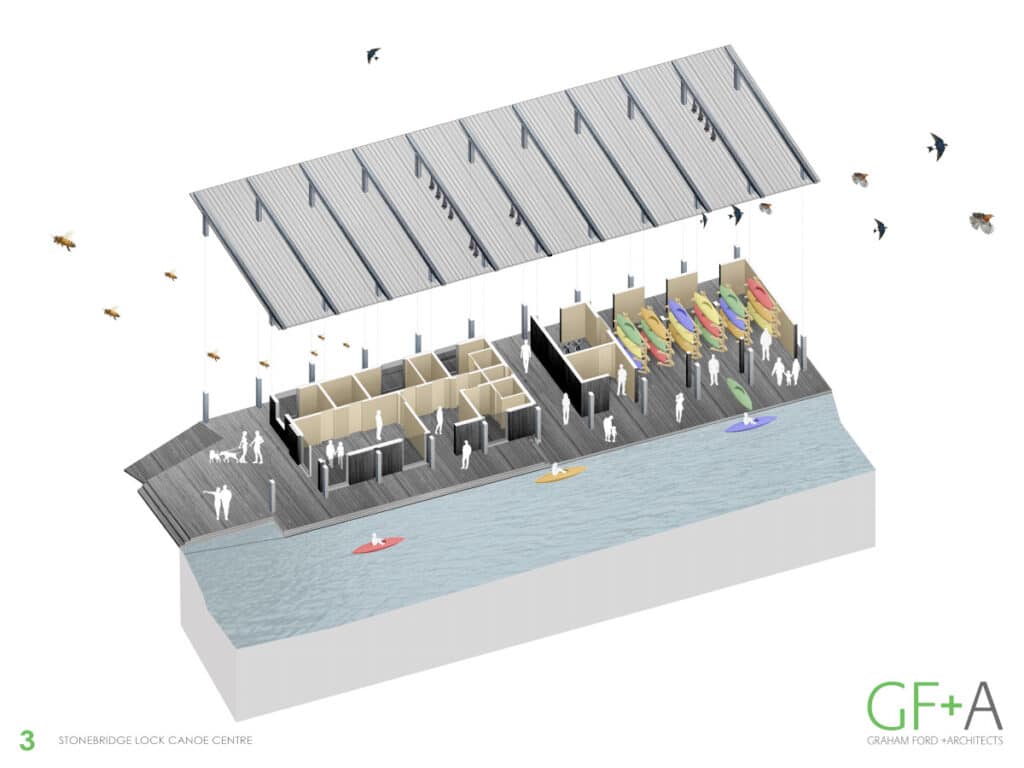

Figure 1 shows Stonebridge Lock Canoe Centre, Tottenham

In order for the Canoe Centre to be considered acceptable in the green belt we needed to demonstrate that very special circumstances existed which would outweigh the harm to the green belt from the new building.

The project is proposed on the site where an existing building once stood. It is currently a brownfield site. To minimise the harm to the openness of the green belt, we kept the scale and footprint of the building as compact as possible with a large opening between the two separate parts of the scheme.

What is required for Development Proposals in AONB?

- Development is generally considered inappropriate unless it can be shown that it will conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the area. Unlike the Green Belt, where the burden of proof is to show “very special circumstances,” in AONBs, the burden is to show that the development does not detract from the area’s beauty.

- Justification for Development: If your development proposal does not automatically fall within the category of “acceptable” development (such as minor extensions, conversions, or repairs that are in line with the area’s natural beauty), you must justify how it will meet the conservation objectives of the AONB. In these cases, the planning authority may still allow development if it can be shown that:

The development is needed for economic, social, or environmental reasons that outweigh the harm to the area.

The benefits of the development to the local community or economy are substantial enough to justify the harm.

It would have a minimal impact on the natural beauty and can be appropriately mitigated (e.g., through landscaping or sensitive design).

What happens to the value of your site when you gain permission?

This is the first major hurdle you might face on your project. The value of your site will significantly increase once planning is granted, so gaining planning permission is a major milestone.

Stages of planning permission

What are the key principles for gaining planning permission?

Principle 1 Analysis of site and policy.

Site Analysis

It also involves a thorough assessment of the site, parking, coverage of buildings, trees, buildings, topography, hydrology, flood risk, location of neighbours and overlooking. It also involves assessment of any buildings on your site. Special attention is paid to historic buildings.

During this site analysis stage, we will do an initial Landscape Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA) and assess where the key views are so that we can determine the potential impact of the development.

A LVIA will probably be required for applications both in the Green Belt and in AONBs.

A Landscape Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA)

A Landscape Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA) is a process that evaluates the potential effects of a proposed development on the landscape and on views and visual amenity.

LVIAs are typically conducted by landscape architects or specialist landscape consultants with expertise in understanding landscapes, and visual impacts.

An LVIA has several components:

- Landscape Assessment that Focuses on the physical and character impacts on the landscape itself, including changes to landscape features (e.g., trees, topography, water bodies).

- Impacts on the character of the landscape, including how it may affect tranquillity, historic landscapes, or distinctiveness.

- Visual Assessment that examines the changes to people’s views and visual amenity, considering the impact of the development on specific viewpoints, such as roads, public rights of way, homes, and key landmarks. The visual assessment will help determine how noticeable the changes will be.

Accurate Visual Representations AVRs or Verified Views

Verified views are highly accurate, photorealistic visualizations used as part of the LVIA process to illustrate what the proposed development would look like from specific viewpoints. They are created using precise survey data, photographic evidence, and 3D modelling to ensure a high level of accuracy.

Accurate Visual Representations AVRs will show what your proposed development will look like in the real world.

They are used to show how the development integrates with or alters the existing landscape and views and are used to assess the magnitude of visual impact.

AVRs and Verified Views are frequently requested as part of the planning application process.

The process for verified views.

- The first step is to take what is known as a ‘baseline’ photo taken from pre-selected locations.

- After the photography site visit, a qualified surveyor will visit all the viewpoint locations and gather GPS readings to generate point cloud data for objects within the baseline photos.

- The final point cloud is used to visually align the virtual model with the actual photograph in model space, prior to the photomontage creation.

- Using GPS topographic survey data, gathered during the site visit, the architect’s computer model is positioned in the real-world model space occupied by the virtual cameras.

- The final stage of the creation process is to merge the accurate camera-matched model with the corresponding baseline photo. Highly detailed renders are produced in the modelling software. These are then composited with the baseline photos in photo editing software.

Planning Policy Analysis

Analysis involves assessing planning risk so it can be mitigated as soon as possible.

Each planning application should be interpreted in context, as solutions that work well in one area may not be acceptable to the local authority in another.

All submissions should be designed to fit the particular circumstances of your site. The analysis will commence in the feasibility stage, and we will strategise how to tackle the seemingly unresolvable tensions that can exist in projects in the green belt and AONBs.

Each AONB is subject to its own local development plan or management plan that outlines the specific objectives and policies for the area. These documents will guide planners in evaluating the impact of proposed developments and will set out what types of development are permissible and under what circumstances.

There will be several issues that you and your design team need to consider in depth:

- The bulk and size of the development.

- The impact on the natural light available to neighbouring properties.

- Any increase in traffic and noise that may affect the area.

We use our knowledge of both national and local planning guidance, including relevant local transport and environmental policies, to make decisions about what we think will be possible to achieve on your site.

It is important your team is thorough in the analysis of all policies to ensure something of key importance is not missed.

Principle 2: Exceptions and VSCs

Once the site has been assessed and local and national policy is understood, then you and your team will need to understand what the exceptions and very special circumstances are so the project can be assessed against policy.

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) notes that the construction of new buildings in the Green Belt is inappropriate. However it does list exceptions to this which include:

- The provision of appropriate facilities for outdoor sport, outdoor recreation, cemeteries and burial grounds and allotments.

- The extension or alteration of a building provided that it does not result in disproportionate additions over and above the size of the original building.

- The replacement of a building, provided the new building is in the same use and not materially larger than the one it replaces.

- Limited infilling or the partial or complete redevelopment of previously developed land.

Your team will need to acknowledge if your proposed development, including new buildings, and extensions to existing buildings complies with these exceptions. If not then you will need to demonstrate that very special circumstances exist that clearly outweigh the harm to the MOL/ green belt.

Below in the Case Study section, I have set out how we built a story supporting a development in the Green Belt and together with our client identified the VSCs for the project. The project is located in the London borough of Kingston.

Principle 3 Storytelling

Your success in building a convincing value proposition is through storytelling. The story you present to the public needs to outline how the project will benefit the community. This is particularly important if you are building in the Green Belt.

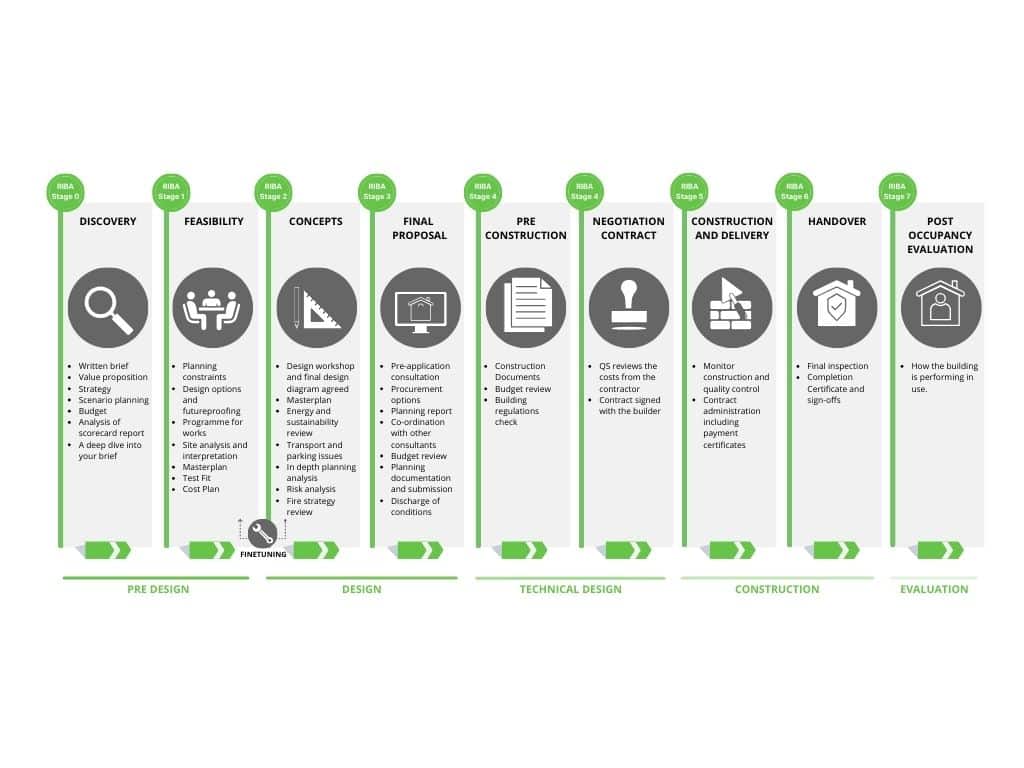

Storytelling work begins in the discovery and feasibility stages and will be explained in the Design and Access Statement (DAS) written and compiled by your architect.

The DAS is a comprehensive report outlining the process that has led to the development proposal. It is presented in a clear and structured way in a written document with diagrams.

The DAS forms part of the documents produced in the Final Proposals stage that are submitted to the local planning authority (LPA).

Your design team needs to anticipate everything that the LPA will consider relevant.

It presents a convincing argument as to why planning permission should be granted, and it is where your team can explain the value of your project in detail, including the economic, social and environmental benefits of the scheme.

The Very Special Circumstances or (VSCs) that are identified will be critical to story that you and your team are developing.

The more compelling your story, the better your chance of success.

Sustainable design must be central to your story about the site and your interventions and changes to the site in both Green Belt and in AONBs. Developments that minimize energy use, utilize sustainable materials, and maintain harmony with the landscape are more likely to gain approval.

Principle 4 Collaboration

The fate of your planning proposal is in the hands of planning officers and/or the planning committee.

One of the potential advantages of a system as complex as planning is that through dialogue, empathy and negotiation it is possible to pick up hints, read between the lines and make the changes required to get your project over the line.

Consultation with the local authority is essential in all complex projects so that both you and your design team can fully understand what all the constraints are, and can benefit from the local authority planner’s knowledge of the area and the local design guides.

To successfully navigate planning, you should commission your architect to build a great team of professionals, including a planning consultant, engineers and a transport consultant, who have ideally worked together in the past.

Since AONBs are designated areas, it is important to engage early with relevant authorities such as Natural England or the AONB Unit. They will provide advice on the application and ensure that it aligns with the AONB’s management plan and conservation goals.

What can you do:

Build relationships: Having a good relationship with local councillors and planning officers and discussing your project with them to gauge support for your proposals will help you assess if there is likely to be significant opposition to your proposals.

Undertake a pre-application meeting: This is a meeting with the council where you can discuss in depth the project and gain feedback from the various experts within their team. Normally the pre-application meeting takes place in Concept Design Phase.

Principle 5 Re-Design

Once we have collaborated with, listened to and received feedback from all the interested parties, particularly the local planning authority. Your project may need to be reworked and transformed to accommodate the feedback. This occurs in the Final Proposals Phase. Only then can the scheme be submitted for planning.

Important note: You and your team need to be flexible and be able to adjust and sometimes rethink applications to consider the views of the local authority. If there is a blockage you need to speak to an experienced design advisor to help.

We offer this service to help clients unlock projects and gain the permissions they need.

Tip 1: Engage a full team to consider all aspects of the application

Why is this important?

If you don’t engage a full team, then vital aspects of the project may not be adequately interrogated during the early stages of a project.

If vital aspects of the proposal are not considered at the right time this can lead to major problems including re-working of drawings down the line. This costs money and time.

Our key collaborators on complex and large projects in Green Belts include:

Planning consultants advise on planning policy and what is likely to be acceptable at a very early stage. They are not always required but typically they are invaluable in green belt projects. We will advise if they are needed.

Some engineering input maybe required for a commercial project. A good environmental engineer can help us to achieve your energy and sustainability goals and improve your chances of gaining planning permission.

A transport consultant will normally be vital to assessing the impact of any commercial development. If you are proposing an extension to a club or school or commercial building then it will be important to assess the impact of increased traffic on the local infrastructure and residents.

Note: residential applications are simpler and normally do not require a large team.

Tip 2: Community Engagement

Why is this important:

Make sure your team helps you consult with the local authority. This is essential in a densely packed urban setting in a conservation area. If you do not take into consideration the views of local people you may fail to capture their concerns and the social value in the project. Your architect can advise how to approach public consultation.

Tip 3: Carefully consider landscape and biodiversity as well as the urban context.

Why is this important?

This could be key part of your scheme if your building sits in a landscape or park. Landscape plays a key role in views to your scheme, the approach to the building, the types of spaces that are between buildings and the richness of the biodiversity of your site.

If your project is in the green belt biodiversity net gain (BNG) will be an issue you need to address. Green belt projects normally need an ecologist who can assess biodiversity.

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/biodiversity-net-gain

Tip 4: Articulate the Social Value of your project.

Why is this important in the Green Belt?

Social Value is used to demonstrate and evaluate the impact of design on people and communities. It includes the social, environmental and economic benefits to society that are a result of your project.

The challenge is to identify the unique context for each development and brainstorm with all members of the team what will being the greatest value to the users of the spaces and the community around them.

The design and its social value can then be discussed with the wider community during consultation and then modified as required. Creative and innovative approaches are needed to deliver social value.

These will form part of your story and be articulated in the DAS. This is important in a commercial project and would not normally be part of a householder application.

The social value of architecture includes:

- Developing connections with nature.

- Offering opportunities for an active lifestyle.

- Creation of jobs and apprenticeships.

- Wellbeing generated by design and healthy communities.

- Designing with the community and creating local employment.

- Learning developed through construction.

- The wider community benefits from the asset.

- Focus on placemaking and creating places for the community to meet.

- Creation of employment for young and disadvantaged people.

- Creating opportunities for training and local employment.

- Preservation of cultural heritage and identity through renovation fostering a sense of continuity and pride in the community.

- Do you believe the building might reduce crime rates in the local area, reduce social segregation or provide employment?

- Does the design help the community connect, reduce loneliness and isolation?

- Creating a safe and comfortable place for people with a range of disabilities including autoimmune disorders (people with allergies for example).

To measure social value better, assessments are required that don’t rely solely on quantitative elements but include qualitative aspect including the evaluation of the impact of projects on wellbeing for example.

What can you do:

Consider Social Value from the beginning: Our advice would be to consider the social value of your project from the outset. This will help guide your thinking and the development of your brief to the design team. The design team will then be able to take your initial ideas and develop these into a compelling story for your application.

Case study

To see how these principles and tips have been applied to a project, see River Club case study, here.